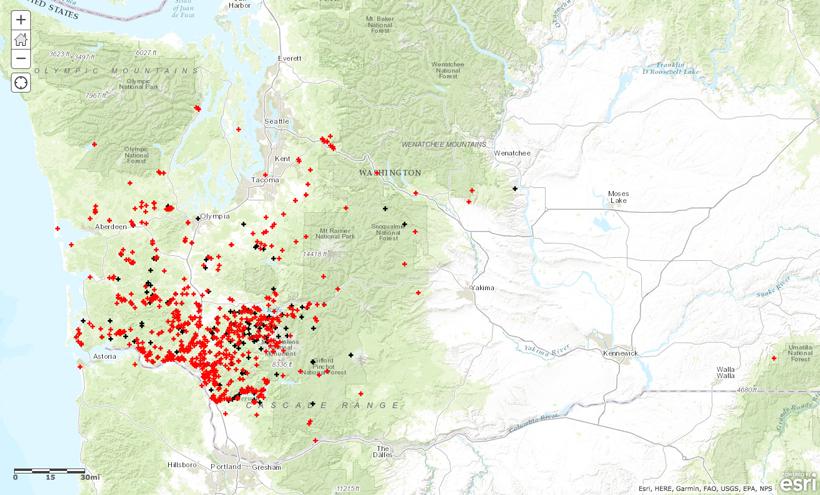

Publicly reported limping elk or dead elk with hoof deformalities from 2012 to present. Red = Limping Black = Dead Source: WDFW

Elk hoof rot lesions. Photo credit: Han, S., K. Mansfield, et al. (2001 in draft)

Photo credit: Jason Phelps

Track from a hoof rot elk in snow. Photo credit: Jason Phelps

Olympic elk are well camouflaged within the thick timber and brush of the Pacific Northwest. Spooked elk may sound like draft horses trotting through the woods; other times they remain silent while crossing the saturated forest floor. They keep you on your toes. Collectively, Western Washington hunters will agree: you smell them before you see them.

On the west side of the Cascades, their terrain consists of dense timber, hills, valleys, and tidelands. The Olympic Peninsula Mountains experiences the heaviest rainfall in Washington (up to 200” per year); whereas, the average rainfall in the lowlands is around 80” annually. Roosevelt elk are larger bodied yet have smaller antlers than Rocky Mountain elk and are found on the eastern side of the Cascades.

For the graphs below, notice the large difference on the y-axis for average annual precipitation from western to eastern Washington.

AVERAGE ANNUAL WASHINGTON PRECIPITATION

AVERAGE ANNUAL PRECIPITATION FOR WEST OLYMPIC COAST AREA OF WASHINGTON

AVERAGE ANNUAL WASHINGTON PRECIPITATION - CASCADE MOUNTAIN AREA

AVERAGE ANNUAL PRECIPITATION FOR SPOKANE AREA OF WASHINGTON

In the early 1990s, a major threat to the Roosevelt herds manifested, incubated and exploded.

Digital dermatitis is believed to be the cause of “hoof rot,” a disease caused by the treponema bacteria known to thrive in wet climates. The disease has been documented to plague livestock, but had not yet been seen in wildlife until then. Fortunately, it is curable through doses of antibiotics and proper upkeep of the hooves (but the likelihood of that happening on wild animals is slim to none).

Hoof rot causes an elk’s hooves to grow abnormally. They become deformed by growing into one another, increasing in length and develop lesions. Sometimes, the disease leads to the loss of the entire hoof. The extent of the disease makes elk limp until they are unable to walk and feed. When they can take no more, the elk lie down for the last time and eventually die of starvation and dehydration. Elk hoof rot has been in the news multiple times the past few years. A few news articles can be read below.

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) began receiving sporadic reports of limping elk in the early 1990s, but Kristin Mansfield, a WDFW wildlife veterinarian, says, “There are a lot of things that can cause an elk to be limping.”

“These reports were few and far between and, ultimately, weren’t setting off alarms with WDFW,” says Mansfield. Officials received more reports in the western part of the state compared to the eastern because of the wet climate. Using domestic cattle as a model, the disease has been proven to transfer from cow to cow; however, state officials do not yet know how it is transferred from elk to elk. Elk often travel in a line and this formation is what biologists believe could transfer the disease from one elk to another.

Source: KOIN News

Nearly two decades later, the state was flooded with an explosion of reports that prompted the WDFW to investigate. So far, biologists have narrowed down what they believe to be the epicenter of the disease: the Willapa and Boistfort herds.

For some hunters, this epicenter is in their backyard, and something they have never seen before.

Jason Phelps, avid elk hunter and owner of Phelps Game Calls, recalls when the elk he grew up hunting stopped walking and started limping.

“That’s been the biggest frustration,” says Phelps. “Willapa hills and my backyard were the first documented areas. We had it for 22 years, and it crosses a line then someone starts caring. It would have been easier if they caught it early on and not now.”

Research is continuously being conducted on how to approach the situation. Mansfield says that the state is working with collaborators to better understand the disease. Scientists at the U.S. Department of Agriculture are still studying the effects it has on cattle and have been “happy” to look at the elk situation and piggy back on one another’s samples of immune response.

“The agency has also taken on a population study that started two years ago,” says Mansfield.

“The effects on survival and reproduction. Are elk more likely to die? Do they die of the same thing normally? And are they less likely to bear calves?”

Regardless of the research that is being done now, outdoor enthusiasts in Washington are both baffled and furious. They say the state did too little too late and acted negligently by waiting so long to act. “Whether they are hunting, scouting, or simply driving by a herd, hunters find it hard to put into words how they feel witnessing elk suffer.,” says Phelps.

The majority of elk habitat in Western Washington is owned by timber companies, though farmers with plenty of fields also make up elk habitat. WDFW has not researched herbicides or chemicals being sprayed because the disease has an epicenter that spreads out, says Mansfield, which are characteristics of an infection.

“The hooves they have examined show infection, not toxicity. Histology results have shown an increase in white blood cells, which are released when fighting a foreign organism,” says Mansfield. “The evidence was right off the bat.”

Toxicity or infection, a mammal’s body will release white blood cells to attack the invader. The state reassures hunters that this bacterium apparently only affects the hooves and that the meat and organs of the elk are safe for human consumption.

For the 2015-2016 hunting season, WDFW created a regulation requiring hunters to remove the hooves of elk taken in affected areas and leave them on site (not to be transported away from the unit). This applied to GMUs 501-564 and 642-699.

“They implemented that new law; no samples, no nothing,” says Phelps. “People were wanting to get third party testing done, and why not? Get someone involved who may be working on their Master’s degree. Generate funding for a third party. Now it’s like they’ve thwarted that effort from the get go.”

Track from a hoof rot elk in snow. Photo credit: Jason Phelps

If the bacteria persist in wet soil and this law was created to minimize the spread of the disease, shouldn’t anyone entering these GMUs be leaving their boots as well?

Each time Phelps sees a herd of elk, he cannot help but wonder what this will eventually turn into. Is that herd still going to be there? He thinks of not only his young children, but the next generation of hunters and would be prospective hunters.

“We need 100% recruitment to maintain our privilege to hunt,” says Phelps. “They ultimately need to be successful to stay interested. We need to be able to pass it on to everyone that comes behind us.”

In January of 2014, hoof rot crossed the border from Washington and into Oregon. The first confirmed case was in Washington County, OR. There have also been isolated cases affecting Rocky Mountain elk on the east side of the Cascades. Throughout the state, 18 animals have been confirmed to have the bacteria and there have been over 60 reports of limping elk. However, hoof rot in Oregon appears to be more scattered than Washington State.

But that is how it began in Washington: sporadic reports that didn’t raise any alarms.

If the ailing elk are indeed suffering from the bacteria, what, if anything, can be done to save them? It is not practical to think that each confirmed case can be administered antibiotics and receive proper hoof treatments like domestic animals. Even then, how much human intervention can be done in regards to safeguarding the elk and their contact with humans?

There may not be a miracle cure, but something must be done. Whether that lies in public outcry, outdoor organizations getting involved, or private funding, this debilitating illness isn’t showing signs of stopping. It’s expanding.

A solution to Washington state's infected elk?