The buck known as Big Ten in 2014. All photo credits: Stephen Spurlock

The Big Ten whitetail buck in 2013.

The Big Ten whitetail buck in November of 2014.

2013 post-rut whitetail buck.

2008 post-rut whitetail buck.

Four-year-old eight point whitetail buck pre rut

Four-year-old eight point whitetail buck post-rut with broken tines.

The scene of the crime.

November 22, 2014 was a tough day. A cold wind blew across the plains of western Kansas. Finally the rut was finally starting to slow and bucks were beginning to become more patternable. The peak of the rut for the western whitetail can result in some pretty erratic behavior which makes archery hunting extremely difficult. As I climbed out of the truck that morning and climbed up into my tree stand for my morning sit, I felt an underlying confidence. I had my mind set on one specific buck and I felt that I was finally getting him figured out. Today something just felt right.

The fall had been a strange one. Beginning with hot temperatures and warm southern breezes, the last week of October and the first few days of November had been a bust. Crops remained in the fields longer than usual and the big bucks of the plains were nowhere to be found.

Trail cameras revealed that the buck I was after had made it through the 2013 season and was still located in his same old stomping grounds. Like the past three years, he remained entirely nocturnal and never made an appearance on camera in daylight, grey light, or twilight. All photos came between 10 p.m. and 4 a.m. The reality was that in three years I had only laid eyes on the Big Ten once. Even then, it was a fleeting glance from the truck one day as I maneuvered around the river bottom early in October to hang a stand. In 2015, I estimated that he had to be about eight and a half years old, which is old by any standard for a whitetail. Since 2012 (when I suspect he was about five and a half years old), he really had not grown much in the rack department. In 2014, he added a small kicker on his g2 but otherwise remained much the same as prior years. His shed antler from the 2013 season revealed that his g2s measured 14 inches — a measurement that truly brought to scope his overall size. As is the case with most large racked animals, his huge body size made judging his rack difficult.

My friends and I had made a conscious effort to harvest this buck since first getting pictures of him in the fall of 2012. Since then, he had survived two archery seasons and two gun seasons. All and all, four hunters from the group I hunt Kansas with each year had tried their luck at him with none of them having so much as a sighting during a hunt. The Big Ten had become a popular topic of conversation in our hunting circle.

The second week of November rolled around and everything changed. Temperatures plummeted from a balmy 60 degrees fahrenheit to -10 in a matter of less than 48 hours. Warm southern breezes were replaced with a brisk north-northeast winds. After four days of sitting in the frigid temps, I made the decision to back off and wait for the buck to establish a solid post-rut pattern before pursuing him further.

In prior years, late November is my luckiest time to hunt and kill big whitetails. Most publications, and many hunters, rave about hunting giant rutting whitetails, but in my limited experience I have found that targeting and hunting one single animal during the peak of the rut to be extremely difficult. They chase does all night and typically end up pinned up with a doe in some hidden location during most of the day. Whitetails seem to choose the most random out of the way places to push the does they are tending. This makes archery hunting them extremely difficult!

As November 18 rolled around, I felt it was time to start checking trail cameras again. Maybe the Big Ten had given the does a break and would be back on a more normal feeding pattern. Unfortunately, the photos were not that great. He was around, but still on a sporadic nighttime pattern. With 10 days remaining before the gun season started, I decided it was time to resume hunting again and hope that he made a mistake.

As the days wore on there were still no sightings of the Big Ten, but on the morning of November 22, something just felt right. Little did I know what the day would hold. The morning passed eventfully as I had a number of younger bucks meander by. Much had changed since my stint of early November hunting. Many of the bucks had broken tines and appeared beat down from the rigors of the rut. All of this meant what I had hoped for: more consistent movement patterns during the post-rut. The morning passed with two good encounters with bucks that thoroughly tested my resolve. One was a four-year-old eight pointer with excellent mass. By this point of the season he had broken a couple of tines so I decided to pass. The other buck that I passed on was an overly aggressive four-year-old eight point with an impressive frame but little in the way of tine length.

I knew in the back of my mind that at any time the Big Ten could walk by. As the morning passed, activity decreased and it became apparent that the Big Ten wasn’t in the section of river bottom where I had a commanding view. Now I could check this areas off from possible places he may be. I decided to move stands midday to a different section of the river that hopefully harbored the Big Ten. I was also worried that the Big Ten potentially could have broken some of his tines by this point in the season since this seemed to affect most of the bucks I saw that morning.

Before the afternoon hunt, I met up with the landowner to check some trail cameras and strategize on the evening hunt. As we moved through the property checking cameras, we came upon a sight no hunter ever wants to see. Tangled in a field ditch was the Big Ten, his antlers locked with a smaller ten point. The battle had been hard fought. Both animals were dead and coyotes had already started their cleanup work. Inspecting the area where the fight occurred, we found blood spread out over an area between 30 and 40 yards. An overwhelming sadness enveloped me as I inspected the scene. The buck fight had occurred less than 100 yards from the stand I had intended to hunt that evening.

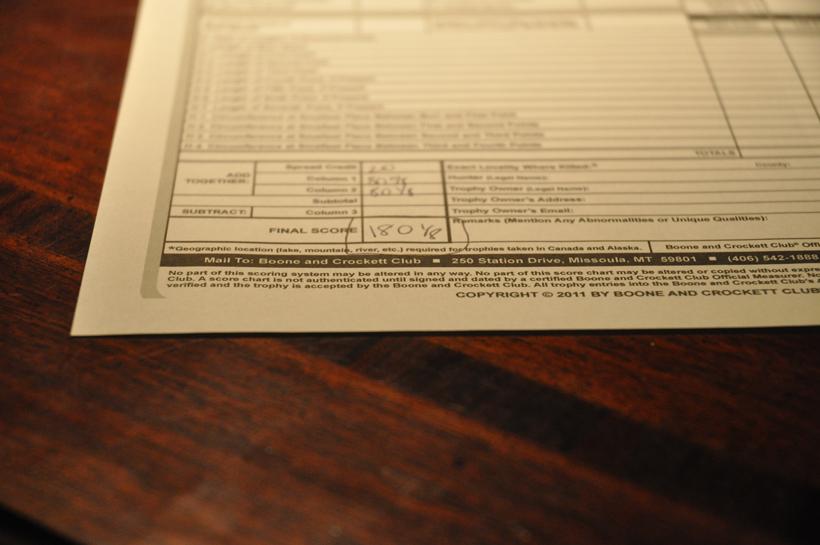

After snapping some brief photos of the bucks “as they lay,” the landowner contacted the Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks, and Tourism and procured a salvage permit for the two bucks.

Once I returned from the trip I had the buck mounted to remember all the seasons spent hunting this specific deer. After taking some time to reflect on my experience with the Big Ten, I plan to make some changes for future hunts that are focused on individual bucks.

The photo below is of a buck I harvested in Kansas in 2011. You better believe this group will be raising a glass to the Big Ten for many years to come. The lessons he taught us all will hopefully stay with us for seasons to come.

I hunted the Big Ten extremely conservatively. I only hunted when the wind was perfect. After reviewing years of notes from hunting whitetails, I have found that I have typically killed mature bucks on a marginal or changing wind. When the wind is perfect you just do not kill them! This concept may be a bit counterintuitive, but take some notes and let me know what you think. The big ones make mistakes when working a crosswind.

I always hunted the Big Ten in November. In hindsight, I wish I had tried patterning him in October or in late December. He may have been more vulnerable during those periods.

Whitetails of the west are prone to pushing does into open prairie country during the rut. Spending more time scouting the canyons outside the river bottom may have turned out a chance at a spot and stalk hunt for the Big Ten.