Photo Credit: Under Armour

Hunters have relied on camouflage (whose name is borrowed from the French word camoufler, "to disguise”) to get them close to animals while on the hunt. However, not all camo is created equal. Just as sights and scouting cameras have changed over time, hunting camouflage has changed considerably in the past 40 years. Here’s a look at the changes we have seen in the evolution of camouflage science.

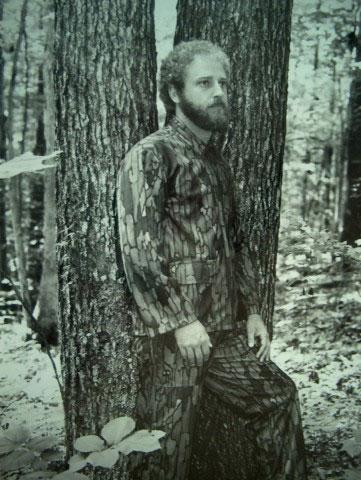

Our hunter camo story begins with Jim Crumley’s Trebark pattern. Created in the late 1970s because military camo didn’t help hunters on American terrain, Crumley dip-dyed and experimented with color to improve his clothes for deer and turkey hunting. The TreBark pattern was finalized in 1979 using images and colors of tree trunks.

Photo credit: Bowhunting.net

Then in July 1980, Crumley ran an ad in Bowhunter Magazine that stated simply, "TREBARK CAMOUFLAGE IS COMING." With that launch, modern camouflage changed forever — and it set the precedent of new patterns being created by hunters with a vision to change the status quo.

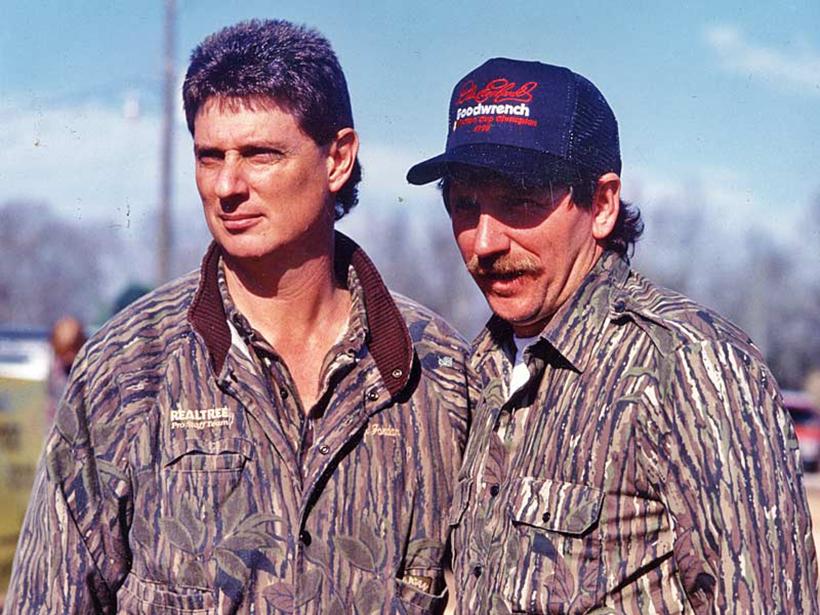

Toxey Haas takes plastic baggies filled with sticks, leaves, and dirt to a textile factory; Bill Jordan sketches trees in his parents' front yard. Shortly thereafter, both Mossy Oak and Realtree started producing camo that looked like trees and foliage in 1986. Their photo-realistic patterns open the doors for a whole new way for hunters to dress.

These patterns work particularly well in the dense, forested conditions of the eastern U.S. The licensing model then led to many mainstream hunting gear manufacturers using these patterns.

ASAT Camo, also founded in 1986 by Jim Barnhart and Stan Starr Jr., went in a different direction with a pattern based on curved lines and a tan background; the goal was to create a camo that is usable in all seasons and terrains. "The pattern remains basically unchanged from the original. ASAT is designed to break up the human outline more than anything else," says Ben Guttormson of ASAT.

In 2001 the U.S. Marine Corps unveiled a camo that was pixelated, creating something like visual white noise. These patterns suggest shapes and colors without actually being those shapes. This pattern moved camouflage in a different, high-contrast direction.

The Predator’s Deception line launched in 2001, moving away from a photo-realistic pattern.

Photo credit: Sitka

Sitka and Mothwing’s 2005 Mountain Mimicry pattern collaboration targeted Western hunters, using mountain-appropriate colors. These contrast patterns try to work with how animals actually see, not just how humans think they do.

Hunter camo continues to take inspiration from predator patterning (think tigers, snakes, and African wild dogs) and to use high contrast. Localization of camo is key — as the U.S. military found out, one size does not fit all.

Photo credit: Kryptek

As brands increase their range of proprietary patterns — take KUIU’s Vias and Verde camo, Kryptek’s multitude of colors, Cabela’s Zonz, and the release of TUSX’s Evade OmniVeil in May 2014, and First Lite's Fusion in September 2014 — hunters have more choices than ever.

Photo credit: First Lite

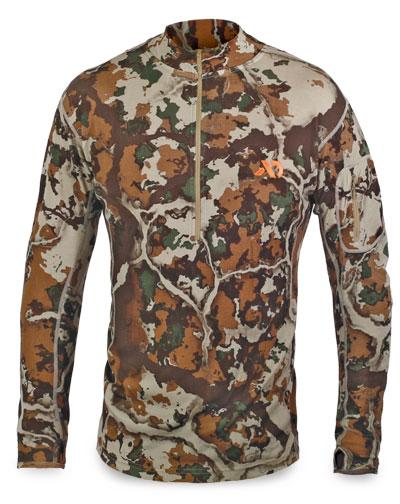

Photo Credit: Under Armour

Even non-hunter producers are getting into the camo game, evidenced by Under Armour’s new Ridge Reaper Barren camo.

What do you see as the future of hunter camouflage? Will the drive for a universal pattern continue? Will localized prints regain stature? Or will technology eradicate the need for patterns completely?