Pronghorn antelope are one of the most exciting species to hunt in the West, and they’re also one of the most rewarding to scout for in advance. Whether you’re preparing for an archery hunt in early August or a rifle season during the September rut, the most successful hunts almost always start with a thorough e-scouting plan.

This guide walks you through Trail's proven e-scouting process for pronghorn, with a focus on water, terrain, and access. The examples here take advantage of the GOHUNT Maps features and tools to make this process much easier.

Pronghorn live in arid, open-country environments. While they get some moisture from the plants they eat, they still rely heavily on water sources like guzzlers, stock ponds, tanks, streams, springs, and seeps.

Finding these water sources before the season is the single most important step in planning a hunt. In late summer, pronghorn are almost always within a couple of miles of a reliable water source, making those spots prime locations for glassing or setting up a blind.

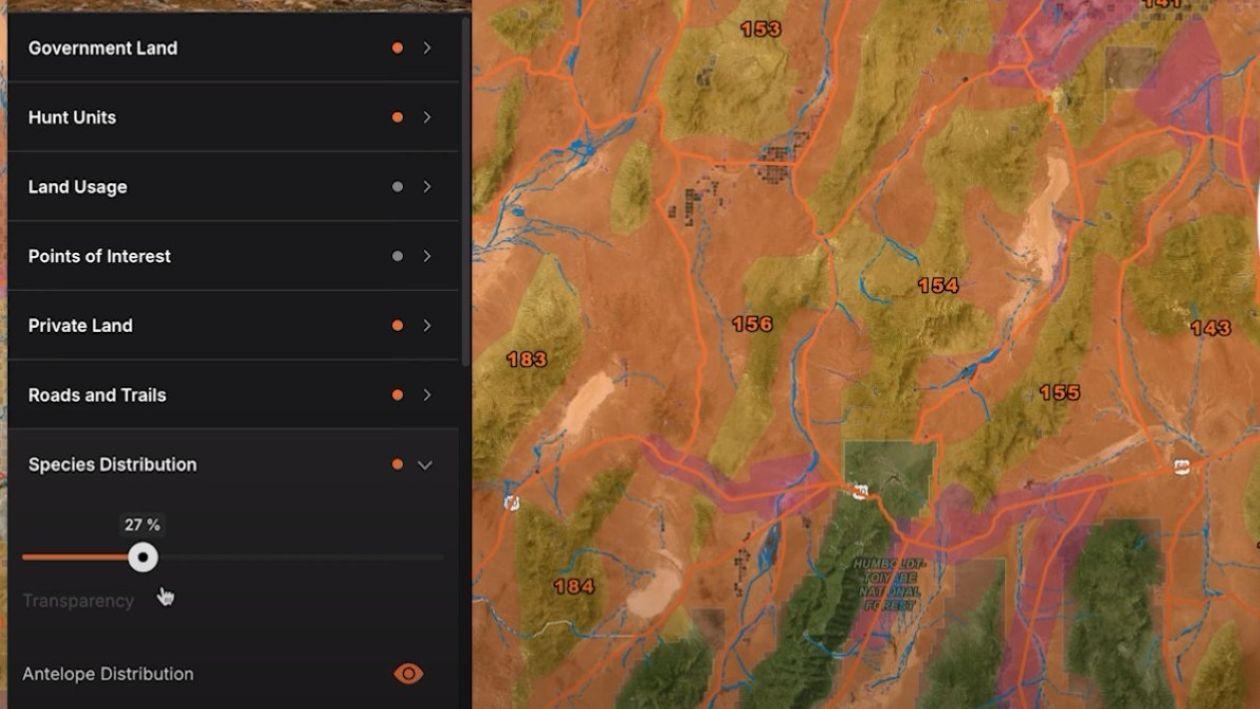

The goal of e-scouting is to create a custom, layered map that highlights high-probability areas for pronghorn activity. Here’s a proven sequence for setting up mapping layers:

Turn on hunt units to clearly mark boundaries. This ensures every bit of scouting effort is focused inside your legal hunt zone.

Make public land layers visible to clearly identify BLM, Forest Service, and state-managed lands.

Identify private parcels to avoid access issues and uncover potential opportunities. In some cases, unposted private land may be legally huntable, and contacting landowners could get you permission.

Western pronghorn hunting involves plenty of driving and glassing. Mapping motorized routes makes it easier to plan travel and maximize scouting time.

These layers show core habitat and migration routes. They can be broad, but they’re useful for narrowing your search in new areas.

Activate guzzler, spring, and river/stream layers. No single database lists every water source, so supplement with aerial imagery to find stock ponds and natural seeps.

Once your core layers are active, zoom in on promising areas. On aerial imagery, water sources often stand out because of:

When you find a waterhole, drop a waypoint and color-code it (blue is common for water). Over time, you’ll build a visual grid of potential pronghorn hotspots.

Before your hunt, visit as many marked water sources as possible:

If you find antelope far from a marked waterhole, use on-the-fly mapping to search for alternative sources nearby.

Even in flat pronghorn country, subtle elevation changes can make a big difference. Use topo maps and the Terrain Analysis tool to find ridges, knolls, and other vantage points near core habitat. Even a 50–100-foot elevation gain can dramatically improve visibility across a sage flat.

Not all water sources hold water every year. Comparing Historical Imagery or Google Earth can reveal patterns:

Cross-referencing these patterns with current-year conditions helps you focus on waterholes that are actually viable during your hunt.

E-scouting for pronghorn takes time but pays off in the field. By layering hunt boundaries, access roads, land ownership, species distribution, and especially water data, you can create a targeted plan before you ever lace up your boots.

Combine this with in-person scouting, glassing, and flexible field tactics, and you’ll dramatically improve your odds of finding and tagging a quality pronghorn buck.

Wagon Wheel Patterns — radiating livestock trails converging on a central point, usually a stock pond or tank.

Bright Soil Disturbance — light-colored rings around a depression often indicate a frequently used waterhole.

Green Vegetation Patches — unexpected lushness in otherwise dry country can mean water is close.

Check for Tracks and Sign — Look for fresh tracks, droppings, and worn trails.

Watch for Other Hunters — Note existing blinds or trail cameras that may indicate "claimed" spots.

Glass the Surrounding Area — Pronghorn are visible from long distances; spotting them confirms a water source’s value.

Which years a pond was full or dry

How precipitation affected water availability

When during the year a water source typically holds the most water