15-20 lbs | |

25" | 700 |

26" | 700 |

27" | 700 |

28" | 600 |

29" | 600 |

30" | 600 |

31" | 500 |

32" | 500 |

20-25 lbs | |

25" | 700 |

26" | 700 |

27" | 600 |

28" | 600 |

29" | 600 |

30" | 500 |

31" | 500 |

32" | 500 |

25-30 lbs | |

25" | 700 |

26" | 600 |

27" | 600 |

28" | 600 |

29" | 500 |

30" | 500 |

31" | 500 |

32" | 400 |

30-35 lbs | |

25" | 600 |

26" | 600 |

27" | 600 |

28" | 500 |

29" | 500 |

30" | 500 |

31" | 400 |

32" | 400 |

35-40 lbs | |

25" | 600 |

26" | 600 |

27" | 500 |

28" | 500 |

29" | 500 |

30" | 400 |

31" | 400 |

32" | 400 |

40-45 lbs | |

25" | 600 |

26" | 500 |

27" | 500 |

28" | 500 |

29" | 400 |

30" | 400 |

31" | 400 |

32" | 350 |

45-50 lbs | |

25" | 500 |

26" | 500 |

27" | 500 |

28" | 400 |

29" | 400 |

30" | 400 |

31" | 350 |

32" | 350 |

50-55 lbs | |

25" | 500 |

26" | 500 |

27" | 400 |

28" | 400 |

29" | 400 |

30" | 350 |

31" | 350 |

32" | 350 |

55-60 lbs | |

25" | 500 |

26" | 400 |

27" | 400 |

28" | 400 |

29" | 350 |

30" | 350 |

31" | 350 |

32" | 300 |

60-65 lbs | |

25" | 400 |

26" | 400 |

27" | 400 |

28" | 350 |

29" | 350 |

30" | 350 |

31" | 300 |

32" | 300 |

65-70 lbs | |

25" | 400 |

26" | 400 |

27" | 350 |

28" | 350 |

29" | 350 |

30" | 300 |

31" | 300 |

32" | 250 |

70-75 lbs | |

25" | 400 |

26" | 350 |

27" | 350 |

28" | 350 |

29" | 300 |

30" | 300 |

31" | 250 |

32" | 250 |

75-80 lbs | |

25" | 350 |

26" | 350 |

27" | 350 |

28" | 300 |

29" | 300 |

30" | 250 |

31" | 250 |

32" | 250 |

80-85 lbs | |

25" | 350 |

26" | 350 |

27" | 300 |

28" | 300 |

29" | 250 |

30" | 250 |

31" | 250 |

32" | 250 |

85-90 lbs | |

25" | 350 |

26" | 300 |

27" | 300 |

28" | 250 |

29" | 250 |

30" | 250 |

31" | 250 |

32" | 250 |

90-95 lbs | |

25" | 300 |

26" | 300 |

27" | 250 |

28" | 250 |

29" | 250 |

30" | 250 |

31" | 250 |

32" | 250 |

95-100 lbs | |

25" | 300 |

26" | 250 |

27" | 250 |

28" | 250 |

29" | 250 |

30" | 250 |

31" | 250 |

32" | 250 |

25" | 26" | 27" | 28" | 29" | 30" | 31" | 32" | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

15-20 lbs | 700 | 700 | 700 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 500 | 500 |

20-25 lbs | 700 | 700 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 500 | 500 | 500 |

25-30 lbs | 700 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 400 |

30-35 lbs | 600 | 600 | 600 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 400 | 400 |

35-40 lbs | 600 | 600 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 400 | 400 | 400 |

40-45 lbs | 600 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 350 |

45-50 lbs | 500 | 500 | 500 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 350 | 350 |

50-55 lbs | 500 | 500 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 350 | 350 | 350 |

55-60 lbs | 500 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 350 | 350 | 350 | 300 |

60-65 lbs | 400 | 400 | 400 | 350 | 350 | 350 | 300 | 300 |

65-70 lbs | 400 | 400 | 350 | 350 | 350 | 300 | 300 | 250 |

70-75 lbs | 400 | 350 | 350 | 350 | 300 | 300 | 250 | 250 |

75-80 lbs | 350 | 350 | 350 | 300 | 300 | 250 | 250 | 250 |

80-85 lbs | 350 | 350 | 300 | 300 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 |

85-90 lbs | 350 | 300 | 300 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 |

90-95 lbs | 300 | 300 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 |

95-100 lbs | 300 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 |

When it comes to bowhunting there are many factors in nature that will always be out of our control. Conversely, when it comes to our equipment there are many factors we can control and some that can really make a difference when it comes to arrow performance. Every year, I see hunters buy the latest and greatest accessories for their bow and then simply grab a box of arrows with little thought other than “they fly decent” and hit the hills. The arrow is one of—if not the most—important factors when it comes down to successfully filling a tag on a hunt. I mean, you wouldn’t put two-ply street tires on your hunting pickup, would you?

Not that everyone needs to rush out and buy the most expensive “custom” arrows that you can, but there is something to be said for carefully selecting what you will be shooting each fall. This can not only set you up for better accuracy and consistency but forgiveness as well. In the following article, we will explore some of the finer points of arrow selection and cover ways to squeeze every ounce of performance out of your setup.

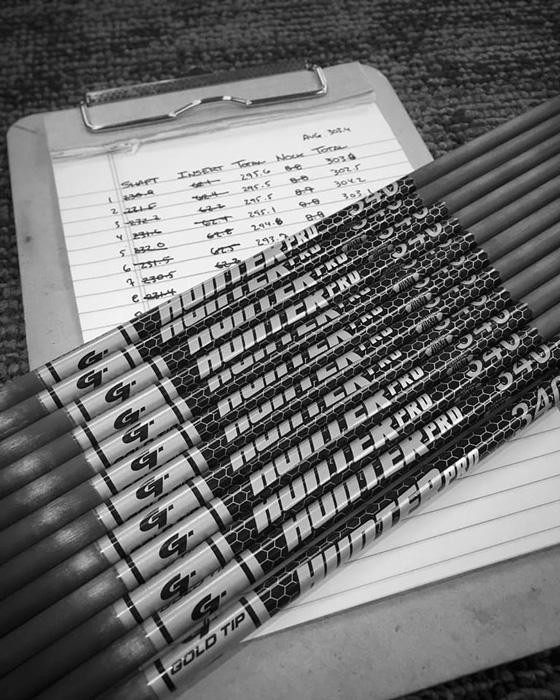

One of the biggest decisions you will be faced with when building a hunting arrow will be the choice between pre-fletched arrows or raw shafts that you, or your shop, will then need to build and fletch. The obvious advantage of going the premade route is that after they are cut to the correct length and the inserts are installed, the arrows are ready to hunt. The downside? You lose all control of consistency and are at the mercy of the manufacturer.

Now, I’m not here to say that if you purchase premade shafts you are destined to be plagued with accuracy issues, I know many hunters who go this route and have great luck each fall. This can merely be related to handloading ammunition; you simply have higher control over more factors and can squeeze every ounce of forgiveness and accuracy out of your setup.

For a very detailed breakdown how to build your own custom hunting arrows from start to finish, check out part one and part two of this informative article by GOHUNT’s Brady Miller.

The simple fact is that the competition within the archery industry is so high that nearly every name brand arrow manufacturer is producing great hunting shafts. In other words, don’t get sucked into only shooting one brand versus another. Instead, consider the game you will be chasing and the specific needs you need from your setup. Once you’ve decided what you want in an arrow, it’s time to start running numbers and see what's out there. I tend to pick a do everything arrow for my hunting in the western US, but there are certain instances where I may tweak my setup for a flatter trajectory or for more penetration.

The explosion of smaller diameter arrows has grown greatly in the past few years and has definitely taken the notice of nearly every arrow manufacturer. Loosely speaking, the smaller the diameter of the arrow, the better the penetration potential and the lower the opportunity for wind drift. Now, this is just a generality and many factors can mitigate these advantages from one arrow diameter to another. One factor to keep in mind is that as the arrow diameter is reduced special insert systems are needed—many of which can require extra attention for proper installation. When considering micro or nano diameter shafts, make sure to research all insert options and decide what best suits your needs.

Arrow spine is one of the biggest issues I see for most archers when it comes to inconsistent shooting and poor performance on animals. Arrow spine in generally reflected in a three digit number and referred to as a deflection, which is usually printed on the arrow shaft itself. Most commonly, you will see numbers such as 500, 400, 340, or 300 though there are some others to be found, depending on the arrow manufacturer. An arrow’s spine is measured by suspending a shaft over a 28” gap and hanging a 1.94 pound weight directly in the middle of the shaft. Then, a measurement is taken over the distance the arrow has bent or sagged due to the weight. So, in the instance of a 400 spine, the arrow has bent or deflected a total of .400” from true horizontal center.

When selecting the correct spine for your setup you will also need to consider factors such as arrow length and head weight. If an arrow is cut longer than 28” the spine will be weaker than the advertised measurement while an arrow cut shorter than 28” will result in a stiffer arrow. Beyond that, as head weight is increased, the spine decreases; a lighter head weight will lead to a stiffer arrow.

Generally speaking, a weak shaft is going to produce inconsistent arrow flight and performance as the arrow is over flexing during flight. This problem is only amplified when you throw broadheads into the mix. Another drawback to a weaker arrow can be found when the arrow actually impacts an animal. When a weak arrow first enters an animal it will contact hide, bone, and muscle tissue and begin to flex back and forth as the momentum generated by the bow fights the resistance of the animal’s body cavity. As the arrow flexes, it will lose forward energy, which can be directly related to penetration potential. In the same situation, a stiffer arrow will experience less side to side flexing and, in turn, focus more of the retained energy into a continued forward motion.

Personally speaking, I always build my arrows to be on the stiffer side of the spectrum as I’ve found these to much more forgiving, easier to tune, and deadly on animals. If you have a nearby shop that sells individual arrows, consider playing with a few setups to find what your bow likes.

All things considered, if you buy a subpar arrow that isn’t straight you can expect similar results when it comes to shooting broadheads. Arrows can generally be broken down into three straightness categories: .006”, .003”, and .001”. That is to say that a .003” shaft can deviate up to 3/1000’s of an inch off of true center. The key to this number is that when most manufacturers measure this they are only measuring the middle 28” of the shaft. Shorter arrow lengths can sometimes lead to better consistency than longer lengths on the same shaft.

For the most part, at distances under 40 yard,s a .006” shaft is going to provide acceptable performance; however, you will find more arrows per a dozen that will fly inconsistently. When you start talking about accuracy at distances exceeding 50 yards you are going to find much better performance in a .003” shaft and even more in a .001” shaft.

Personally, I use the straightest I can buy as this only leads to less tuning time needed on the range and leads to more time learning and perfecting my setup.

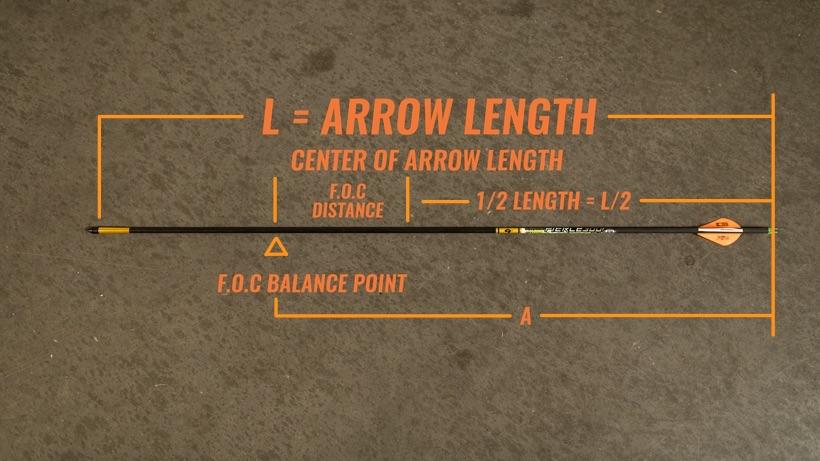

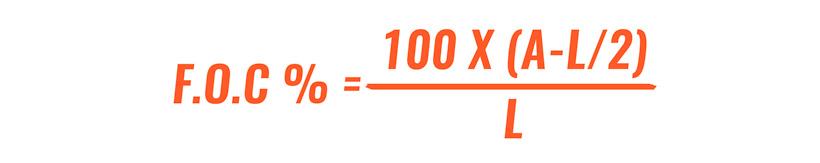

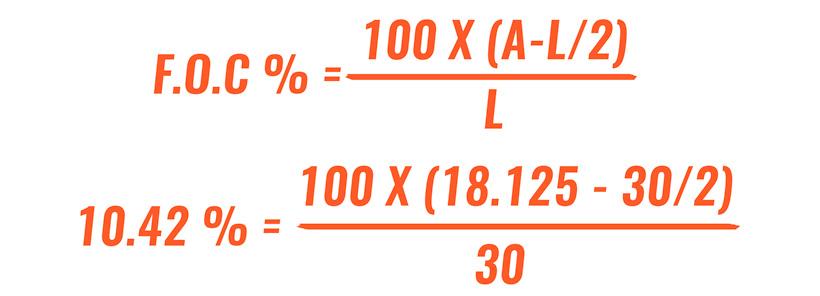

Front of center (FOC) weight can be described as the percentage of arrow weight on the front half of the arrow as measured from a perfect balance point. The topic of FOC has been hotly debated in the past few years and many hunters are pushing towards extreme amounts of weight up front. Some manufacturers have even taken notice and have started offering heavy brass or stainless steel inserts weighing as much as 100 grains. For the most part, an average carbon arrow insert will generally weigh between 10 and 20 grains.

When considering building an arrow with a higher FOC, it is also important to consider your arrow spine. As you add weight to the front of the arrow you are now weakening the spine. Thus, you may need to bump up to a stiffer spine in order to achieve optimal performance from your bow.

To avoid the proverbial beating of the dead horse I will simply state that I have personally had great results with heavier head weights and have found the forgiveness, accuracy, and consistency a welcomed effect.

Step one

Install all the components you will be using on the shaft (points/broadheads, vanes, inserts, nock, etc.).

Step two

Measure the arrow's overall length from the bottom of the nock groove to the end of the shaft and divide by two. In this example, the overall length of the measurement is exactly 30 inches then divided by two would be 15.

Step 3

Find the perfect balance point of the full arrow (point, fletching, wrap, nock, etc.) using a sharp edge. In this instance, a knife blade was used.

Step 4

Mark the point, and measure from the throat of the nock. In this example, the measurement is 18.8125 inches.

Step 5

Subtract the center of the balance point (18.8125) from the center of the arrow measurement (15). Multiply the resulting number by 100. Then divide that by the overall length. For this example, the arrow's F.O.C is 10.42%. Adding weight to the back of the arrow will decrease F.O.C. and adding weight to the front of the arrow will increase F.O.C.

The choice of fletching will largely boil down to whether you are buying premade arrows or building your own. When going with premade arrows you will find the venerable Blazer vane by Bohning Archery on 95% of the available options. The Blazer and other high profile vanes have become incredibly popular due to their inherent ability to steer a broadhead tipped arrow. These high profile options provide more steering than some of their lower height counterparts and can help cover up some shooting flaws when conditions are less than ideal.

When I fletch my own personal arrows I like to use vanes in the 3” length with a lower height profile than a typical Blazer vane. The extra inch of surface area length makes up for the lack of height in steering while the lower profile allows for a quieter arrow flight.

A common question I often hear from other hunters when they prepare to fletch their own arrows is whether they want a straight, offset, or helical fletching pattern. For the most part, the faster an arrow spins the more forgiveness your setup will allow. In other words, a helical fletch will shoot better when you torque your shot versus a straight fletched arrow under the same circumstances. Most factory fletched arrows will generally be fletched in a straight pattern though many are starting to come in a slight offset or helical. At the very least, I recommend to all of my customers that they at least go with an offset pattern as this will afford good hunting performance. The one downside to more rotation? Your arrow is going to slow down faster than an arrow that spins slower. However, with my hunting setups, I’ll take a slower and more accurate arrow any day. You can read more information here.

Research anything about “the perfect hunting arrow” online and you will find pages upon pages of hunters debating the correct weight of a hunting arrow. When it comes to arrow performance on animals there are so many variables from impact angles to muscle density that I feel that the posed question of what arrow weight is best is entirely impossible to answer. The main thing I try to convey to hunters is to shoot a weight you are comfortable with and have confidence in.

Generally speaking, an arrow of 400 grains or more will kill anything in North America when put in the right spot, but certain situations can dictate the need for something more or less.

As I stated at the beginning of this article, I like to build a “do-all” hunting arrow for out West; something that can be applied to any hunting situation I may encounter. Over the past few years, I have shot arrows ranging from 415 to 480 grains and have found the best performance for my setup towards the upper end of that spectrum. Again, to reiterate my original point, find an arrow that makes you happy and shoot, shoot, shoot. Familiarity and confidence in your equipment will be much more deadly than what Bob from down the street thinks you should shoot.

Along with arrow weight, you will find the battlefront of online debates involving broadheads to be quite substantial. When selecting a broadhead, I like to first list out features that I’ve liked and disliked from previous heads. Obviously, in-field experience can aide in this, but, just like arrow weight, trust your gut instincts. Confidence is key. 95% of the broadheads on the market—both fixed blade and mechanical—will effectively kill 100% of the animals in North America. I personally prefer fixed blade broadheads in a four blade configuration, but I always keep mechanical broadheads handy and often carry them in the same quiver. Instances when terrain or the target animal may dictate longer shots in less than ideal conditions (thinking sheep, mountain goats, or high country mule deer), I will always opt for the more forgiving mechanical broadhead. Conversely, when hunting thicker country where nearly all of my shots will be a top pin endeavor, I will favor a reliable fixed blade head.

Another common question is whether or not archers need to have their blades aligned with the arrows vanes. This will likely be a debate, but the resounding answer from me is no! Sure, when building arrows from scratch, I will align everything for consistency's sake, but the alignment of the blades has absolutely nothing to do with accuracy. Instead, focus your time on ensuring each broadhead is spinning correctly, without wobble, on the end of your arrow.

All thing considered, when your bow is perfectly tuned, your arrow is correctly spined, and your form is correct, you will see fixed blade broadheads fly right with your field tips out to any given distance.

Whether you are choosing to buy raw shafts or premade arrows a little understanding of what you are looking at can make a huge difference. Examine your current setup and ask yourself, “Am I happy with this or do I know that I can build something better?” There are so many options in arrows and components today that an archer can find endless possibilities and enjoyment in trying new setups and discovering what works best for you and your bow. Find what gives you confidence and carry that with you on your adventures this fall!