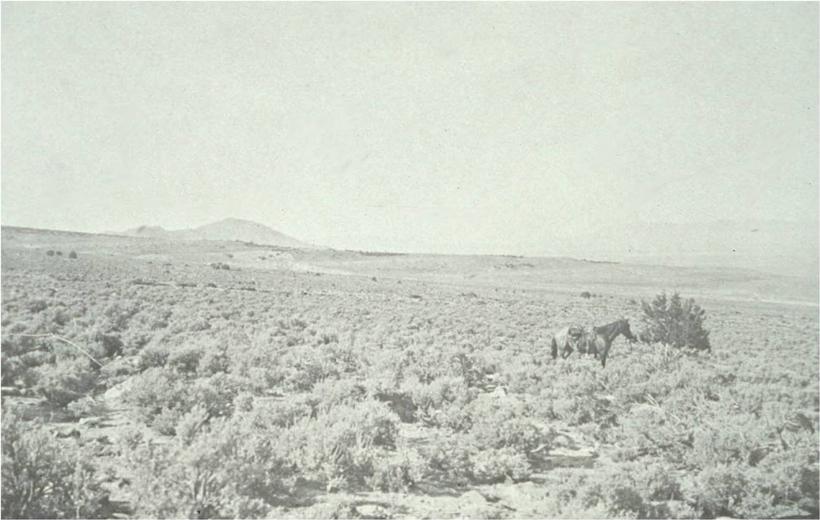

Stansbury Mountains in 1901. Source: Utah UDWR

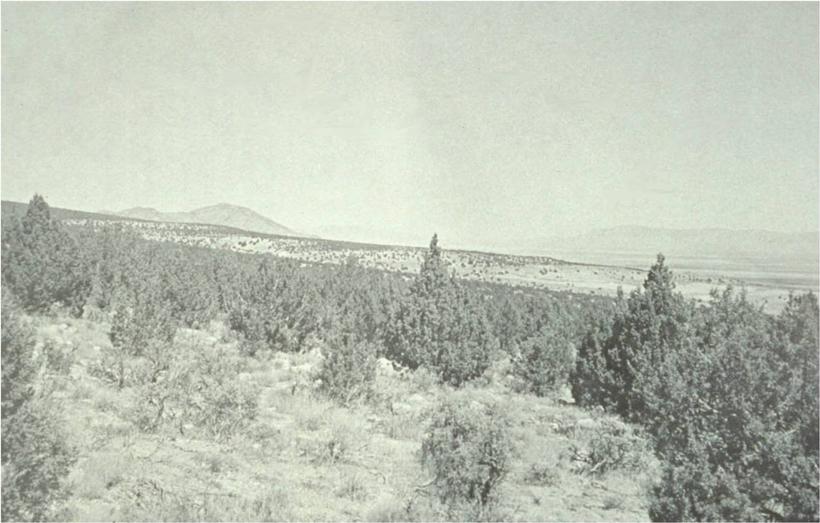

Stansbury Mountains in 1976. Source: Utah UDWR

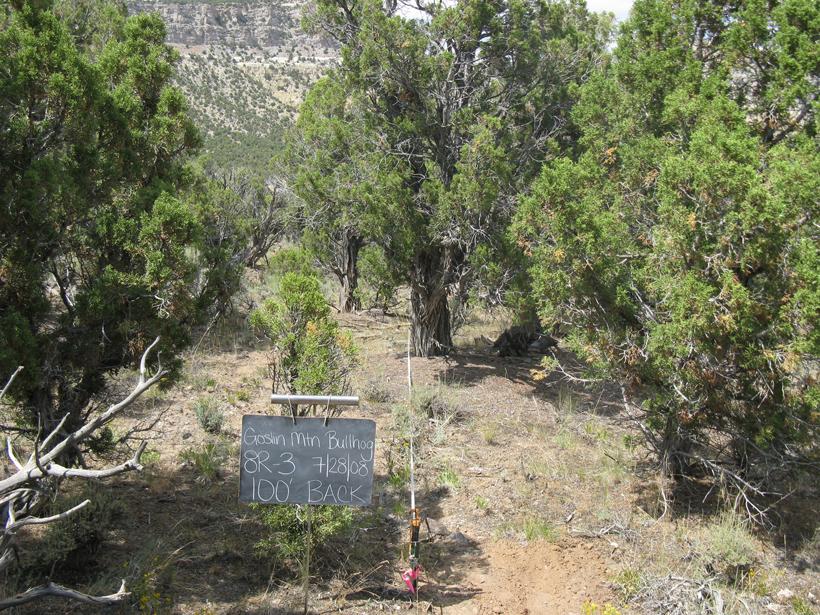

Photo credit: Trail Kreitzer

Decade | 1920s |

|---|---|

Acres burned | 26 million |

Decade | 1930s |

Acres burned | 39 million |

Decade | 1940s |

Acres burned | 23 million |

Decade | 1950s |

Acres burned | 9 million |

Decade | 1960s |

Acres burned | 4 million |

Decade | 1970s |

Acres burned | 3 million |

Decade | 1980s |

Acres burned | 4 million |

Decade | 1990s |

Acres burned | 3.6 million |

Decade | Acres burned |

|---|---|

1920s | 26 million |

1930s | 39 million |

1940s | 23 million |

1950s | 9 million |

1960s | 4 million |

1970s | 3 million |

1980s | 4 million |

1990s | 3.6 million |

Chaining to improve habitat. Photo credit: Trail Kreitzer

Aerial seeding. Photo credit: Trail Kreitzer

Bullhog creating better habitat. Photo credit: Trail Kreitzer

2008 Goslin Mountain before the habitat bullhog. Photo credit: Trail Kreitzer

Goslin Mountain in 2013 after bullhog. Photo credit: Trail Kreitzer

Wildlife guzzler. Photo credit: Trail Kreitzer

Across the west, stories about the legendary mule deer hunts from the 1950s and 1960s are being retold and discussed as mule deer populations continue to decline. But how many of us actually understand the backstory of those robust mule deer populations? Were there always large mule populations across the West or were the “good ol days” of mule deer hunting a culmination of environmental changes and conditions, and if so what were they? If indeed something has changed, can we recreate those original ideal conditions?

The earliest estimates of mule deer populations by early western settlers suggests that populations were low in the late 1800s, but it is unclear what the population numbers were compared to in order to suggest that the herd numbers were low. Studies have shown that population estimates are really only relative to some known high point and for most Western states mule deer population peaked in the early 1950s and 1960s. Biologists in the 1950’s noted fawn/doe ratios of 75 to 100 and even accounts as high as 100 to 100. What happened? How did we go from low populations in the late 1800s to extremely high populations fifty some years later?

A very good example of the transitions that have occurred can be illustrated by GOHUNT’s home state of Nevada. Although each western state and local history varies slightly, changes that occurred in Nevada also generally occurred throughout the West. The California Gold Rush and western expansion of Mormon pioneers resulted in the creation of several trails, routes, and eventually railroads. Easier access into new areas resulted in more settlers moving west to claim new lands and carve out a living in the intermountain west. Mining, agriculture, and livestock production resulted in the removal and utilization of vast amounts of timber across Nevada and the West. Timber was harvested to convert forested areas into agricultural and pasture lands. The timber was used to support mine shafts and as, firewood. Because of the extensive timber removal, up to 90% of Nevada’s modern pinyon-juniper trees are less than 150 years old. Two photos below compare the Stansbury Mountains in 1901 and 1976. You can see the vast changes to the vegetation in the photos.

In addition to tree removal, sheep and cattle grazed on public lands across the west at extremely high rates, peaking in the 1920s. Because of mining, agriculture, grazing and several years of consecutive above normal precipitation levels landscape scale vegetation disturbance resulted in seral plant communities ideally suited for mule deer. A seral plant community is an intermediate stage in ecological succession where shrubs occur widely throughout an ecosystem. Shrubs are critical for mule deer since they are a ruminant like elk or cattle, but differ in the fact that their rumen is much smaller in relation to their body size. While elk and cattle do well by consuming massive amounts of low quality grasses mule deer must be more selective in what they eat and choose high quality young sagebrush, bitterbrush, forbs, and green perennial grasses. Although unintended, these early industries and the associated landscape changes created the perfect setting for mule deer habitat expansion and population growth.

The latter half of the 20th century has brought a steady barrage of change that has negatively impacted mule deer populations. Roads, freeways and expanding development has fragmented and interrupted the large areas of mule deer range. Predator management changed and the poisons once utilized to remove predators were outlawed and resulted in a surge of natural predators. While human expansion and an increase in predators likely affected the mule deer population, the most detrimental factor has been environmental changes to the natural habitat that began with the major fire suppression efforts in the 1950s. This brief look at the fire data will give you an idea of how extreme the reduction in burned acres has been.

But is fire a bad thing? Remember that mule deer are an early successional species that thrive when disturbance sets the ecosystem back to young palatable plants. Fire suppression has done three things. It has allowed the shrubs that do exist within the system to age and become less palatable and less nutritious. Second, it has allowed millions of acres to move from an early successional state to a climax state where trees dominate most sites. While trees are great for thermal cover, they rarely offer the nutrition that deer need to survive and reproduce. Third, fuel loading has increased and with increasing fuel loads, fires burn more intensely, which results in a recovering plant community that is less diverse both in species, age class and often areas then become dominated by invasive exotic weedy species.

Cheatgrass invasion across the west has been particularly detrimental, specifically on winter ranges. The characteristics of cheatgrass allow it to out compete native bunch grasses and shrubs. It also cures early in the year which in turn increases the fire regime and burning is needed more often so that it does not allow shrubs to reestablish.

Healthy aspen communities have been replaced by conifer stands. Mountain shrub, shrub steppe, and grasslands have been replaced by Pinyon and juniper. Trees out compete grasses, forbs, and browse species that are crucial for wildlife and livestock. Because of this reduction in forage, land management agencies have reduced livestock grazing on public lands.

Together these factors have negatively impacted mule deer and the overall population of current herds.

It is likely that past resources no longer exist and cannot be recreated at previous levels to produce record numbers of deer. We have to face the hard fact that mule deer populations of the “good ol’ days” are gone, but that does not mean the deer are facing troubling times. In fact, populations seem to be thriving thanks to recent mild winters. While we may not get back to where we once were, I certainly expect that better days are ahead. Almost every western state has kicked off landscape scale restoration efforts within the last ten years that should continue to help boost herd growth.

For example, in 2004 the Utah Watershed Restoration Initiative was developed as a partnership between land and resource management agencies and conservations organizations to develop, fund, and implement landscape scale restoration projects. The UWRI has developed a project database where biologists and resource specialists work together to design and propose habitat restoration projects annually. The projects are ranked by a committee representing all participating parties and high priority projects receive funding. The funding for these projects comes from a combined pool of federal, state, private, and conservation organization funds. This has allowed for larger landscape projects to be completed.

Since 2004, the UWRI has completed over 1.1 million acres of restoration work in UT with more projects continuing in 2015. Nearly 140 million dollars has been funneled into projects that focus primarily on the removal of encroaching Pinyon and juniper, restoring sage steppe habitats through reseeding. Numerous water developments, wetland, riparian, fire restoration, wildlife highway fencing and underpass projects have also been completed to assist in the overall conservation efforts.

While the undertaking has been massive, what, if anything, has it done for deer? As a habitat biologist, this is a question I get asked a lot. So, here is my professional opinion. If you look back at the history of mule deer, large landscape disturbances were conducted heavily during the very early 20th century with populations peaking later in the 1950s.

While it is human nature to want immediate returns, it is important to consider the big picture and look back at the history. Everything takes time. Based on known succession, land disturbance responds with grass and forb production first before developing into shrub or scrub habitats that mule deer prefer, especially on winter ranges.

With large landscape scale habitat work a focus in the early 2000s and continuing since, we may be headed toward better days of deer production and hunting, but it may take a few more years or longer to see the benefits of the current focus on habitat restoration. As a father of three young boys, I’m confident that they will continue the mule deer hunting tradition and it is likely that they will have even better opportunities than me.

If you would like to get involved with the Utah Watershed Restoration Initiative you can check out their website. Here you can review projects, see the participating partners and find links to other great information. Also feel free to stop in at a local Utah UDWR, BLM, USFS, NRCS office and talk to a habitat or resource specialist.